Whitton War Memorial Stories

Walter Watts

Walter Watts was the first recorded casualty of the First World War from Whitton, who lived at 54 Hounslow Road. He was part of A company 1st Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment and was killed in action on 18 September 1914, aged 21 during the First Battle of the Aisne.

The Battle of Aisne began on 13 September In dense fog when British and French forces crossed the River Aisne. Their objective was to attack German forces who held one of the most commanding and formidable positions on the Western Front.

Neither side could move the other and neither chose to retreat. On 14 September, British forces were ordered to entrench, despite the soldiers not having been trained in trench warfare nor having the necessary entrenching tools available. Local farms were scavenged for tools and shallow pits to provide cover gradually evolved into the trenches that became synonymous with WW1.

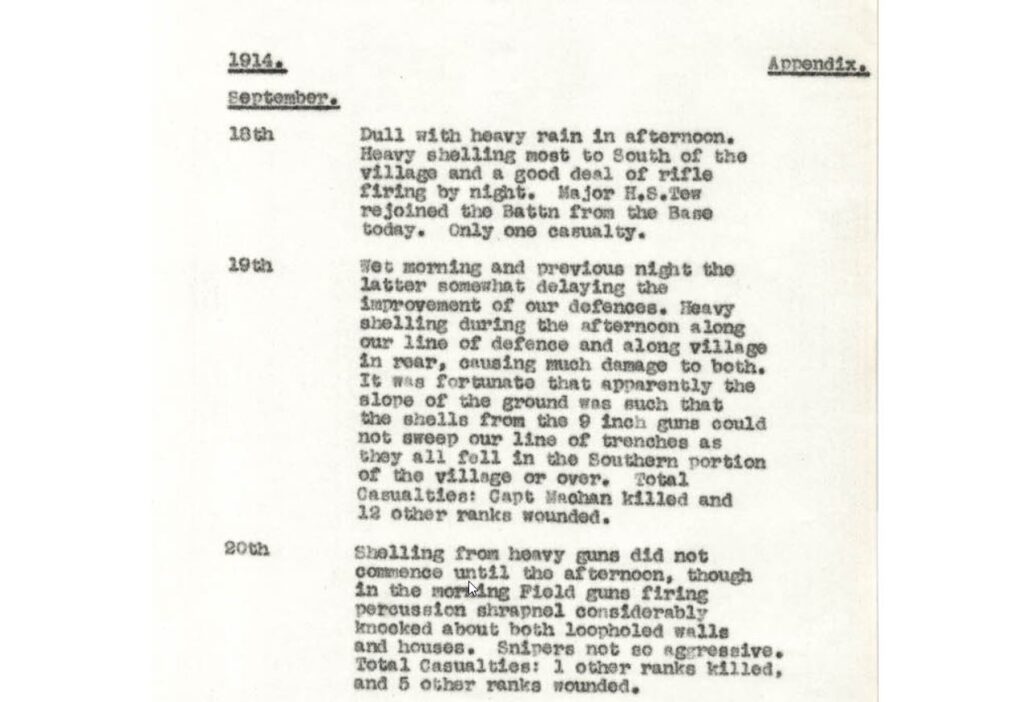

The Germans were similarly not prepared for trench warfare, but they adapted quicker than their British counterparts. Siege howitzers, trench mortars and hand and rifle grenades began to take a significant toll on allied forces, without the ability to reply until new weapons were hastily deployed. Walter Watts was killed on the 18 September and was the only casualty that day.

‘Dull with Heavy Rain in the afternoon. Heavy shelling most to south of the village and a good deal of rifle firing at night. Major H.S.Tew rejoined the Battalion from the base today. Only one casualty.’

Battalion Diary on the day of Walter’s death

Harry Ketchell

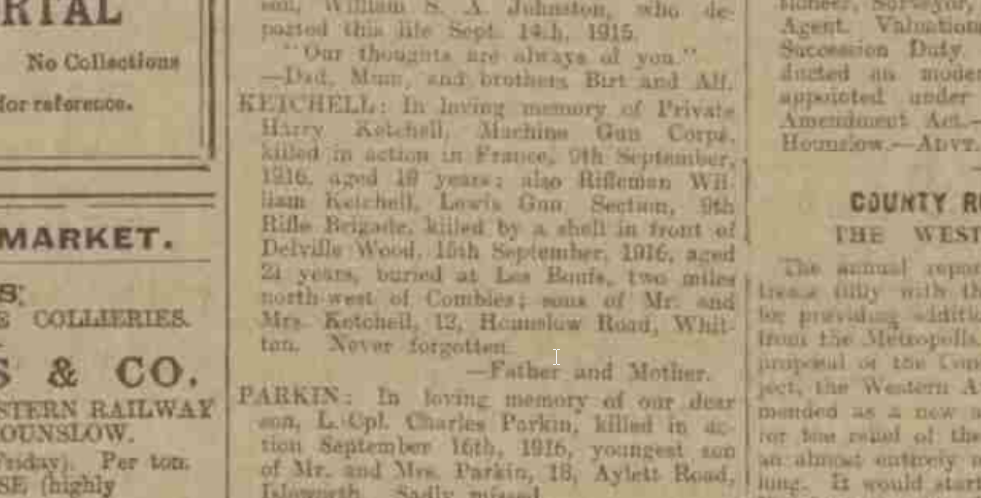

Harry Ketchell lived at 12 Hounslow Road with his parents James and Emily and 4 other siblings, four boys and one girl. He was a private in the 164th Machine Gun Company and was killed in action on 9 September 1916 in the Somme offensive.

The Machine Gun Corp was formed in September 1915, recognising the need that the employment of machine guns required specialist training, skills and tactics. The Corp shortly after acquired the new Vickers gun, a 26kg gun that could fire 500 rounds a minute. Generally, a Vickers machine gun team would be made up of between six and eight men, two to carry the gun, two the ammunition and two spare men.

Harry Ketchells’s machine gun company was attached to the 55th West Lancashire Division during the Somme offensive, which began on 1 July. After various actions which resulted in 4,126 casualties the division returned to the front on 4/5 September, again close to Delvile Wood salient. Harry took part in the Battle of Ginchy on the 9 September and was killed on this day, alongside seven other members of the 164 Machine Gun Company. The village of Gincy was captured the following day.

George Ash

George lived at 7 Prospect Crescent and was the son of George and Minnie Ash. He was a Private in the 8th Battalion of the East Surrey Regiment and was killed in action on 12 October 1917 aged 20.

He was killed participating in the First Battle of Passchendaele. The attack was part of the Third Battle of Ypres and was fought west of Passchendaele village and took place on 12 October.

The Battalion moved up to the front line on the night of 10/11 October, but got lost and arrived late. Orders for the attack had been issued to company commanders, but these changed, and updated orders could only be given to commanders at night. Many didn’t receive them, one platoon couldn’t be found at all and was only located once they began the attack.

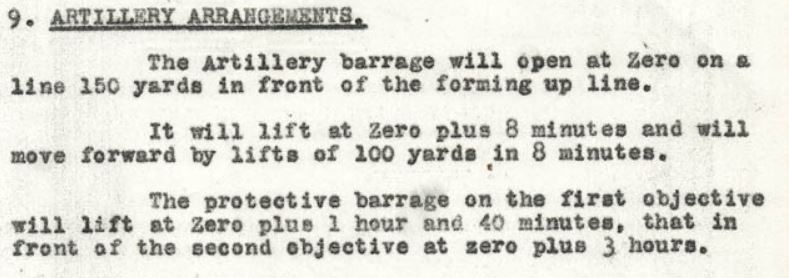

The preliminary artillery barrage began 4 minutes before the attack, but enemy machine gun fire immediately began to open up on the British positions and wasn’t touched by the artillery. British soldiers described it as being “too light and the enemy wasn’t inconvenienced by it at all.”

Progress made by the attack was minimal. Whilst a report of men having advanced up to 500 yards was received, none of the soldiers who survived the attack describe being able to advance more than 100 yards.

The attack was hindered by the condition of the ground, which was heavily waterlogged. The mud was so bad that quick rushes from shell hole to shell hole were impossible and most casualties amongst officers and NCOs were as a result of them trying to organise advances. Soldiers hands were caked in mud, which made its way into the rifles everytime a clip was changed, meaning that rifles had to be cleaned every few rounds.

Every officer in the battalion except three had become casualties, alongside many NCOs and any runners that tried to relay progress to HQ were gunned down by the enemy. It became clear that despite some isolated advances the majority of men had made very little progress and the line was reorganised 100 yards from the starting point. The Battalion was relieved that night having suffered 56 killed, 142 wounded and 42 missing. George Ash included amongst them.

John Bowden

John Stanley Frank Bowden was born in Twickenham, Middlesex, United Kingdom in 1898 and lived at 45 Colonial Avenue. His job Job before the war was as a market garden labourer, He was a Boy First Class in the Royal Navy and served aboard HMS Chatham.

HMS Chatham was detached to operate in the Red Sea when the war began in August 1914. In May 1915 the ship returned to the Mediterranean to support the Allied landings at Gallipoli. In 1916 she returned to home waters and joined the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron of the Grand Fleet.

On 26 May 1916 HMS Chatham hit a mine off the coast of Harwich. The ship was damaged sufficiently that it had to be towed to Chatham for repairs. John Bowden was one of two fatalities, alongside Boy 1st Class Walter Turner. They are buried alongside eachother in Gillingham Woodlands Cemetery. The ship was placed in reserve in 1918. After the war, Chatham was lent to the Royal New Zealand Navy from 1920 to 1924.

WHITTON VICTIM OF THE CHATHAM.

Middlesex Chronicle, 17 June 1916

Whitton has to mourn the loss of another of its sailor boys, John Bowden, of 45, Colonial-avenue. He was serving on board HMS Chatham, which during the Horn Reef week was starting for the East India Station on a three year’s cruise, and when off Harwich struck a mine and was sunk. Young Bowden, who was afterwards picked up, died from the injuries he received, and was subsequently buried at Chatham with full Naval honours.

Ernest Brougham

Ernest Brougham – Lived at 5 Colonial Avenue was the son of Arthur and Alice Brougham and was killed in action on the first day of the Somme 1 July 1916 aged 18.

Ernest was a Private in the 13th (County of London) Princess Louise’s Kensington Battalion of the London Regiment, a territorial force mobilised in 1914 and had been fighting in France since 1915.

Their contribution to the Somme offensive, taking place further south, was to participate in a diversionary attack on the Gommecourt salient. Due to the nature of the diversionary attack very little thought had been put into exploiting any gains made. German defences at Gommecourt were very strong, which didn’t make it the most ideal choice for diversionary attack, and no attempt was made to disguise preparations for the attack. Indeed it was a deliberate intention to attract attention and role of the London Regiment was to induce the enemy to shoot at them.

The first objective on the 1 July was to reach the German third trench and create strongpoints. The Londoners with comparatively little loss, were in the German front line before they could be seriously opposed. The first two trenches were easily overrun; but the third, manned by German riflemen was only gained after a fire fight. The first objectives, the three front German trenches were secured.

Unfortunately for the Londoners the assaults either side of them were unsuccessful leaving them alone and exposed to German counter attacks and artillery, which duly arrived. Reinforcements and supplies that were due to arrive later that morning were unable to reach them due to German artillery fire. Over the course of the next few hours German counterattacks would gradually take back the lost trenches until only a single point of the German trench system was occupied by 70 men and 5 officers. This final position was eventually lost and the remaining soldiers returned to the British trenches, where they had started that morning. Of the 24 officers and 500 men who started the attack that morning, 16 Officers and 310 Other ranks were killed, wounded or missing.

John Wells

Ordinary Seaman John Wells was born on 27/4/1886 in Peterfield in Hampshire and was the son of Mr and Mrs H Wells of Heston Middlesex. He lived at 18 Hounslow Road and died on 31 May 1916 at the Battle of Jutland aboard HMS Chester. He was 28 years old and one of 4 Whitton men who died during the battle of Jutland.

He married Florence Elizabeth Wells at Whitton Church on 16 April 1916 and died in action a month later. His name is not on the Whitton War Memorial at St James Church, but is commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial, Kent. His occupation before the war was a gardener working in the market gardens of Whitton.

On 31 May 1916, HMS Chester was scouting ahead of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, a massive formation of 150 British ships. Chester was sent to investigate distant gun flashes amid a bank of mist. Suddenly, four German light cruisers appeared and opened fire, hitting the ship seventeen times. Extensive damage to the ship’s guns meant that she could take no further part in the battle and was ordered back to port. The ship suffered casualties of 35 killed and 42 wounded.

During the shelling the forward 5.5 inch gun position was hit four times, killing or badly wounding all the gun crew apart from the sight setter, Boy (1st Class) John Travers Cornwell. The badly wounded 16 year old remained at his post awaiting orders. Although Cornwell survived long enough to reach hospital in Grimsby, he died of his wounds on 2 June.

In September 1916, Jack Cornwell was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest award for valour in the face of the enemy. His devotion to duty at the Battle of Jutland inspired a huge show of public affection across Britain and 21 September 1916 was named ‘Jack Cornwell Day’ in his honour. The 5.5 inch gun manned by Jack Cornwell and possibly John Wells has been on display at the Imperial War Museum in London since 1919.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Caroline Woods

Could you please add William Watson to a poppy in Whitton high street please , my dad served in the armed forces for 22 years and was with the Royal Scots Greys then went on to serve in the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards, he served in the miltary band .